Critical Perspectives

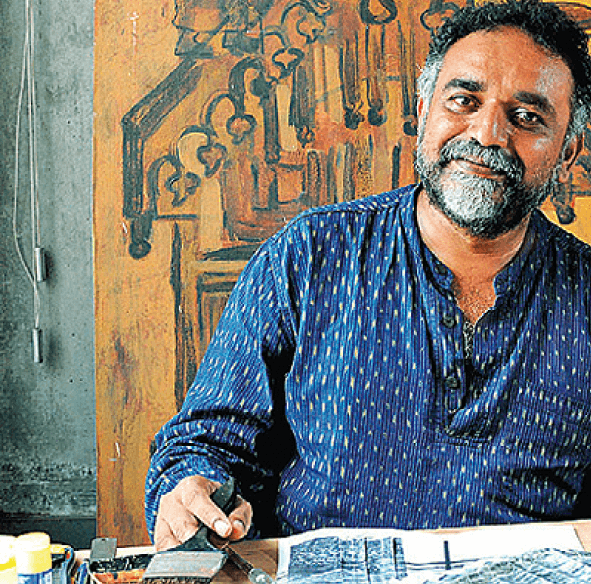

SURESH JAYARAM

Art Historian, Curator & Art Educator

A HUMANISTIC VISION

“My works are generated by my intense feeling for my environment. I seek to find myself by following whatever course it leads to.” – Kattingeri Krishna Hebbar The portraits of K K Hebbar at HGAC are representative of his visual language. Hebbar is one of the most prominent modernist artists in India who was contemporary to the Bombay Progressive Artist’s Group and belonged to a secular cultural landscape of the post Independence Nehruvian era. He belonged to a generation of artists that was self- conscious about their national identity in thought and attitude.

K K Hebbar relocated from his native Kattingeri in South Canara, Karnataka to Mumbai later in his life and this migration of a regional artist to the national arena of an emerging cosmopolitanism – Mumbai can be traced in his works as well. Bombay, a hub of many industries with an enlightened milieu of patrons, was also where the British had established the JJ School of Art. It is here that Hebbar lived and studied under Charles Gerard who asked him to find his own individuality beyond mere technical skills. His characteristic technique of using palate knife and impasto is part of the School of Paris and was popular in his time. Hebbar was known for his ‘singing lines’ where he captured the rhythms of workers, dancers and musicians.

Hebbar’s abilities as a portraitist, to capture the sitter’s likeness and character through observation were remarkable.

He was given many official commissions to paint portraits of distinguished political leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru,

Indira Gandhi, Dr. Shivarama Karanth and others. Among these portraits is a striking self – portrait – a young and

confident artist, his angular features characteristic of a slender man, dignified and elegant in his stature and above

all, a sensitive human being. The series of portraits made by him include his immediate family members, friends, fellow

artists and contemporaries including commissioned portraits of politicians, statesmen and patrons. The styles vary, from

realistic academic style to expressionistic portraits and delicate line drawings. They also vary in mood and medium.

These form a catalogue of significant people he encountered in his own world whom he portrayed with compassion and

immortalized through his art.

Eminent figures such as the cultural polyglot Dr. Shivarama Karanth, writer Vyasaraya Ballal

and the economist, writer K S Haridas Bhat who also penned his biography in Kannada, helped him reconnect to his

South Canara roots. The indigenous quest for a rural identity was an obsession as well as an inspiration for his

paintings that depicted rituals and living traditions. Hebbar’s artistic legacy is thus deeply intertwined with

the vital folk traditions of this region.

These portraits are gifts from the Hebbar family. By this generous gesture, the artist and

his work have returned to his native land like the prodigal son. Re-claimed as a significant figure in the

Indian modernist’s quest for national identity by the regions of South Canara, K K Hebbar is remembered by many

as a visionary and a humanist. – Suresh Jayaram

Read more

TIME, CAPTURE AND PORTRAITS

Before there were photographs, there were portraits. From the time a very early ancestor drew her family on the wall, an act of pure representation of the present or of a hopeful future that would come to be, people have inscribed themselves on flat surfaces. Today a portrait is often seen with the same gaze that one sees a photograph. Most of the time the only naïve gaze and critique of a portrait is about the likeness of the painting to the original person. From a perspective of time how ever I suggest that a portrait is a capture of time as duration rather than of moments. When we see portraits, it is important not to see them as photographs. Unlike the fleeting snapshot of a photograph that somehow locks up those instantaneous moments, freezing them, a portrait by the very process of production seems to have embedded in it a time period in two ways.

The first is the experience of the process of portrait painting by the artist and the subject. The process involves a background against which the subject is painted, and a context of an experience, a period in which the artist and the subject are bound, mediated by Art in a time that is so artificial, so constructed. Yet it is this very length of time that renders portraits as compositions of people, almost entirely dictated by the artist, some lines of the face stronger, a likeness that captures the hours of sittings, the contexts of the times in which the portrait was situated, as well as the subject.

The second embedded duration of time is on the act of painting as a medium. The capture of a likeness again is not an instantaneous act. The paints and textures that render a subject on canvas are not merely mimetic of the real person but they are particularly translated into the canvas through time. This translation of actual colors and vision of a three dimensional object into a flat canvas makes the portrait an interesting study of the art of layering. Each layer of wash is applied in time, a blob of brown taking on the texture of skin, of features, of expression and of living tissue. The portrait much like the person it captures undergoes gestation and one would say is born into being. To understand this art form, I think we need a temporal gaze, not one requires to not merely sift through a portrait gallery but actually give the viewing of each portrait a duration, an unpacking of the process and the acknowledgement of time as passing through the portraits.

Read more

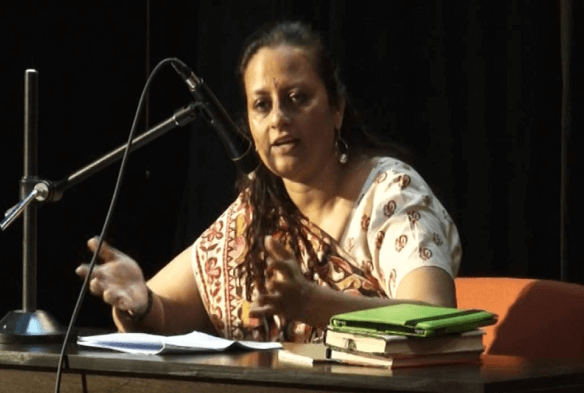

DR. MEERA BAINDUR

Educator

DR. NIKHIL GOVIND

Head, Manipal Centre for Humanities

ART AS ESSENTIAL

K K Hebbar’s mentoring role in institution building, not just in Mumbai, but also in Vadodara, made him a very different figure from the stereotype of the lone artist who might think that talking too much about art destroys the purity of the experience. Indeed, painter K G Subramanyam has spoken of how Hebbar felt it necessary to write and talk about the diversity of experience available in India, for only then could one formulate a resolute and kinetic artistic vista.

Hebbar, whose 20th death anniversary is this year, actively encouraged younger artists and students, always trying to find scholarships for them. So, it is fitting that his family recently donated around 25 artworks (including a sculpture) to Manipal University. It is doubly heartening because although Hebbar studied and spent his life in Mumbai, he came from the Tulu-Malabar region, whose arts such as Yakshagana and Nagamandala were central to his sense of colour, form and dynamic lineation. […]

It would do universities in India a world of good if more such art centres were created by endowments. At a time when campuses are smouldering and there is all-round student alienation and mental distress, spaces for art can play a vital role (of course, alongside traditional and formalised interventions like health centres) in mitigating student fear and apathy.

Art has always had the power to take you out of yourself, and plunge you into a more universal feeling. Unlike a consumable, commercial object, art ideally reawakens a deeper connection with both the cosmic as well as the social milieu. Given the frenetic pace with which ever newer colleges sprout and grow, surely some money and thought might go towards securing support for credible spaces and outreach for art. Perhaps it is not just political parties but artists too who should hover around universities, looking for converts and cadres.

Much more than standalone museums and galleries, campus art centres will benefit from the large student population and the energy that universities provide, while adding to the intellectual ecology of the place, many as a visionary and a humanist. – Suresh Jayaram

Such museums or cultural centres have been central to the history of the more celebrated international universities — one thinks of Harvard and the Peabody, Oxford and Bodleian, and Stanford with its central square of Rodin sculptures. The arts and sciences can mutually reflect each other and grow into each other for the better health of both. Indeed, there is no university abroad worth the name that does not have a strong art presence.

Such centres have both dimensions — on one side is the canon: already famous artists, who are central to a notion of civilisational heritage, beyond the narrow instrumentality of universities as job-training centres; on the other side is the dimension of a live and vibrant centre that continually runs events and programmes, keeping alive the flame of a creative, cultural citizenship.

There were many times when Hebbar was frustrated by the lack of resources, of young, culturally literate aides to help carry out his vision. It would be a happy conclusion if now, years after his death, his work speaks again to students, who may make their way to the horizon he glimpsed.

Read more