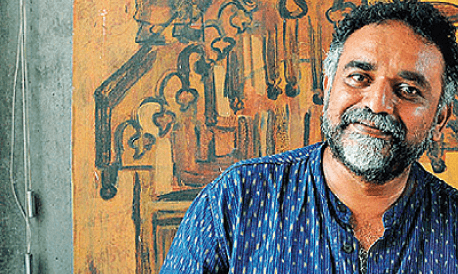

Kattingeri Krishna Hebbar

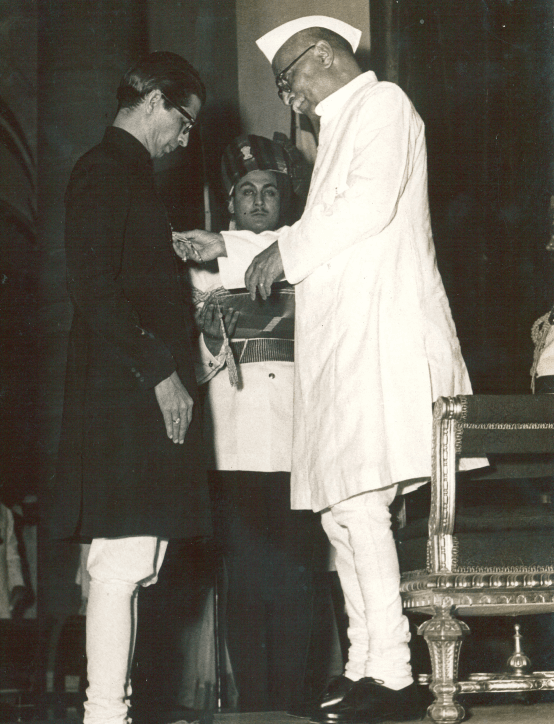

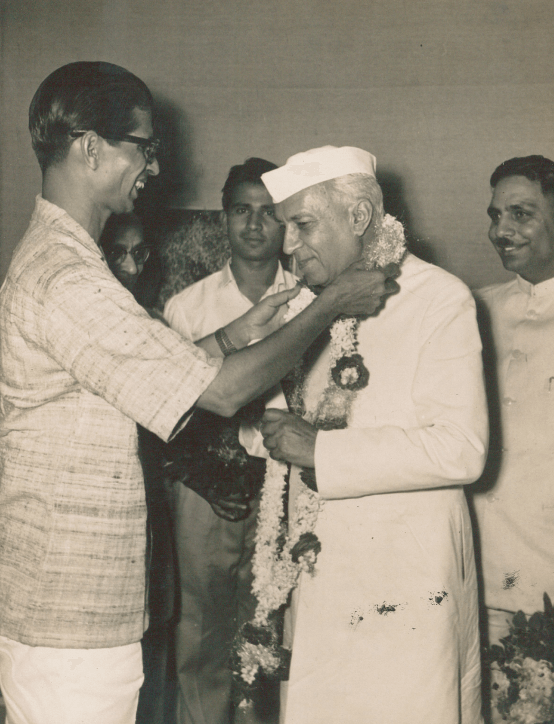

K K HEBBAR WITH PANDIT JAWAHARLAL NEHRU AT THE UNVEILING OF MOULANA AAZAD’S PORTRAIT AT AZAD BHAVAN, 1959

Biography

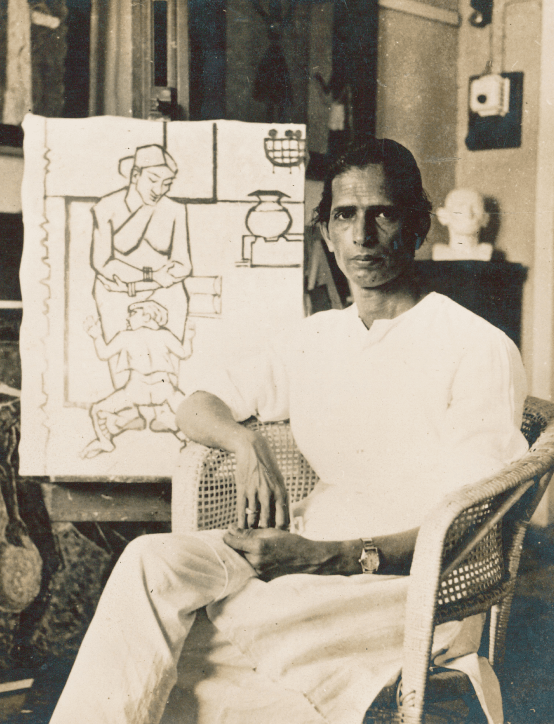

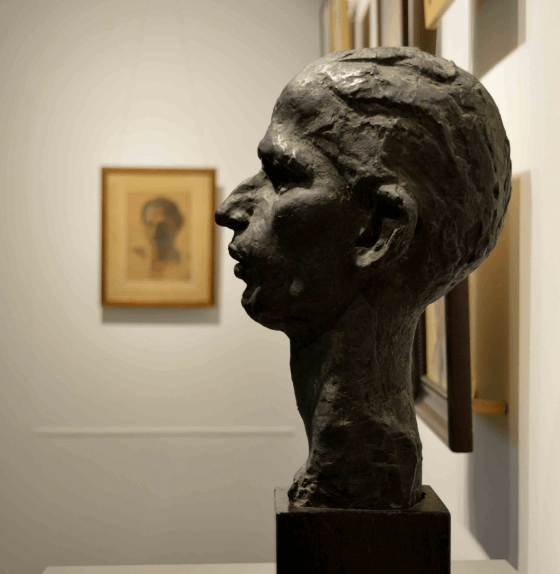

On Portraiture

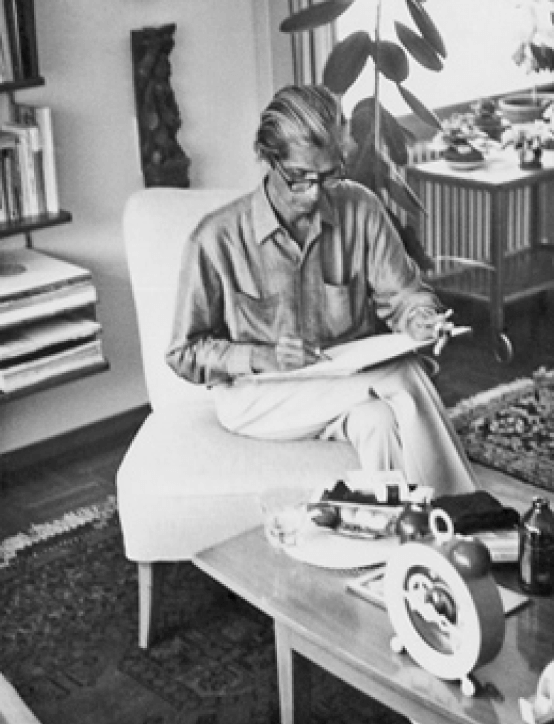

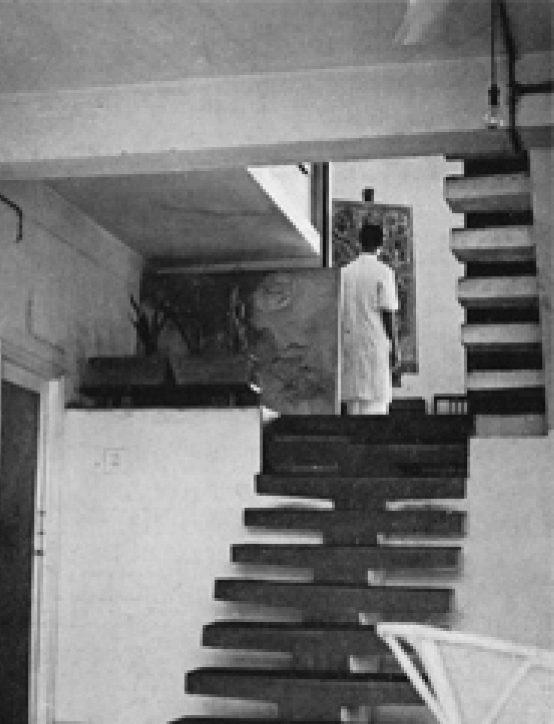

Hebbar’s Aesthetic

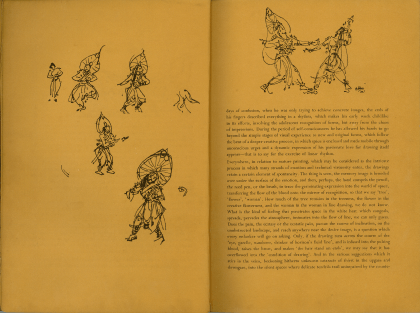

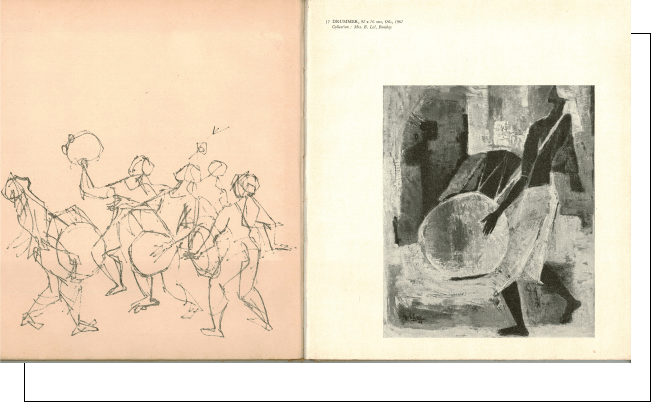

Hebbar hailed from Kattingeri, a village near Udupi and had grown up amidst a musical environment rich with folk performative traditions like Yakshagana. His long standing friendship with the cultural polyglot Dr. Shivarama Karanth who also hailed from the same region is well-known. As a young man, Hebbar had learned Kathak from a disciple of Birju Maharaj, not in order to learn dance, he insisted, but in order to instil a sense of rhythm that would reflect in his art works[1]. His singing lines adeptly captured the vibrant energy of Yakshagana dancers in the elaborate costume, complete with the head dress ( ketaki mudhale) and the breast-plate ( kavacha ). In fact the tiny head dress that was later introduced for the costume of female roles in Yakshagana by Dr. Shivarama Karanth has been attributed to a suggestion from Hebbar.

Awards & Distinctions

Collections

Location

Location Museum

MuseumGovernment Museum Collection

Commonwealth

Collection Australia

Poland

Czechoslovakia

USSR

Dresden Museum

The Staten Island Institute

of Arts and Science USA

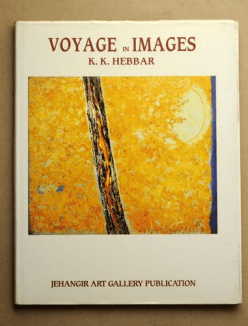

Publications

1948

1948Nalanda Publication, Mumbai

1960,82 (revised)

1960,82 (revised)Contemporary Artists Series by

Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi

1964

1964Publication, Mumbai

1974

1974Publication, New Delhi

1982

1982 Abhinav Publication, Mumbai

1991

1991Mumbai

1999

1999Navakarnataka publication